The world famous Hollywood sign on Mount Lee overlooks the city of Los Angeles, CA.

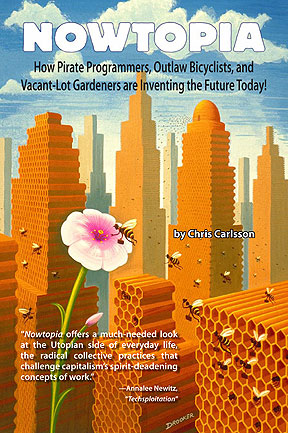

The Llano Del Rio Collective’s Map For An Other L.A. was published in 2010; it was the collective’s first project. It proposed to map the creative and ecological practices that together may have constituted a mysterious city; one defined by creative potential rather then economic relationships. The map described a variety of Los Angeles enthusiasts, they may have had professional lives elsewhere, but came together to; keep-bees, make art, bake bread, glean, communalize food, cycle, present films, hack machines, share, and do-together. The big ideas behind the Other L.A. map was an appreciation for Gibson-Graham feminist economics, and a reading of the Italian Operaismo movement of the early 1970s. The biggest influence on the formation of the Llano Del Rio Collective’s Map was the book Nowtopia; How Pirate Programmers, Outlaw Bicyclists and Vacant-Lot Gardeners are Inventing the Future Today!, written by West Coast Zelig, Chris Carlsson.

Chris Carlsson is for full enjoyment.

Carlsson was a founder of the instrumental magazine Processed World, it published 35 issues between the years 1981 and 2005. Processed World chronicled the rise of, what came to be known as, the neo-liberal economy with a publication, which appeared purposefully to be produced on borrowed time and stolen office materials; this was in part the topics it covered. Carlsson is credited as the progenitor of the Critical Mass bicycle ride in San Francisco in 1992; then called the Commute Clot. Carlsson’s book Nowtopia ties together anarchistic currents into a cohesive politics of work refusal, creativity, hacking, environmentalism, and pleasure-seeking. In 2010, the idea of non-capitalist creative production being a politics was intoxicating, given that Los Angeles was experiencing the twin effects of the economic collapse of 2008 and the rise of the social practice art, discourse, and action. These phenomena had Angelinos experimenting with alternatives to competitive capitalism, and put a premium on collective action and utopian idealism within creative communities. A Map For Another L.A. is a snapshot of that Los Angeles.

How Pirate Programmers, Outlaw Bicyclists, and Vacant-Lot Gardeners are Inventing the Future Today!

Now in 2018, a decade on from the 2008 crisis, the Llano Del Rio Collective is preparing to release its guide Rebel City Los Angeles. Like A Map For Another L.A., this new guide seeks to plot practices that together can constitute an arrangement, pointing at an alternative meaning for the topography of the city. The inspiration of Rebel City is the urban Marxism of David Harvey’s book Rebel Cities, and the “city from below” made visible through the lives of the trans sex workers of Hollywood in the 2015 Sean Baker film Tangerine. There’s a distance between the politics of “the city from below“ represented within the Rebel City Los Angeles guide, and the creative post-capitalism of the Map For An Other L.A.. Yet both guides share the idea that reframing how we imagine the city, holds power.

In the spirit of learning about the distance Llano Del Rio has traveled between these two guides we reached out, via email, to interview Chris Carlsson. We wanted to know where he has gone in the ten years since he penned Nowtopia.

The official seal for the City of Los Angeles.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Robby Herbst) When I first read Nowtopia I saw it as an exciting work of speculative and theoretical geography. You write in your book; “Taken together, this constellation of practices is an elaborate, decentralized, uncoordinated, collective research and development effort exploring a potentially post-capitalist post-petroleum future. “ I’m wondering if you can reflect on the context (economic, theoretical, political, social) that formed your desire to imagine the Nowtopian constellation.

Chris Carlsson) I started working on Nowtopia theoretically many years before I actually wrote it. I had written many articles for Processed World, participated in or covered a variety of labor struggles since the 1970s (from the UFW lettuce boycott, JP Stevens textile boycott, OCAW strike in 1980, Blue Shield strike in 1980-81, PATCO in 1981, Watsonville cannery workers in 1986, etc.), and had been thinking about the pointlessness of work in the capitalist economy for my entire adult life. My few years as a secretary and word processor in banks, accounting firms, brokerages, and software companies in the early 1980s was the point of origin of the magazine project, but the experiences—which dovetailed with a lifetime of busy-work in school settings—have haunted me all along.

In the early 2000s I thought if something called “revolution” is possible, it must be visible in the daily life all around me. I’m not a religious person, and don’t believe in revolution as something that appears out of the blue. So I began to look more closely at how I, and most of my friends and acquaintances, were actually spending our time. It didn’t take a big effort to recognize that most of us were working two or more jobs, even if only one of them was officially “paid,” and recognized as such. Whether as artists, historians, philosophers, writers, parents, political activists, or any of a number of activities that called us, most of us were living a bifurcated life: on one side we had to make money and we found our way to that end, by hook or by crook. But it was when we were NOT working for money that most of us seemed to be most animated, most enthused, most passionate about our “real work”–and on further examination, that work very often took the form of tinkering or repurposing technologies, or working with the discards and waste of modern capitalism, to address the actual problems of modern life.

Thus, the book Nowtopia was written to foreground the self-activity and liberatory impulses that underlay so much of what we do, even if those very same activities and projects were relegated to near irrelevance precisely BECAUSE they weren’t oriented to making money. They did not register as part of GNP. They were done with a commitment to carry them out without monetary remuneration or the usual kinds of rewards that denote “value.”

I also was informed by the notion of “class composition” and wrote about the long decades of post-WWII and then neoliberal reorganization of the global economy, and how that had led to such a profound atomization and fragmentation of daily life, leaving us all more isolated than ever. In these nowtopian projects and work, I saw a glimmer of working-class recomposition, but no longer based on wage-labor or the luck of residency, but rather based on freely chosen activities and the new relationships that were developing and deepening in the carrying out of those activities.

RH) Central to your book is a different take on the concept of class. You eschew more traditional ideas of class affiliation embracing the concept of class composition, and center upon a refusal of work. In this refusal of work, you sight the emergence of something that I might describe as an anarchistic non-capitalist entrepreneurialism of the radical deed. This affective relationship to labor and technology underlie the affective politics of your book. Your book was written before the 2008 economic crisis, before the murder of Oscar Grant, the global Occupy Movement, the northward migration of Silicone Valley, the rise of Black Lives Matter, the Trump presidency, and the #metoo movements. How have these events and the way they speak to more essential racial and class based identities, effected your reading of the possibility for the kind of politics you imagine in your book?

CC) A decade after publishing Nowtopia, I’ve realized for quite a while already that many of my most hopeful prognostications weren’t “coming true.” That is, the emergence of a new self-conscious working class movement based on a refusal of stupid, pointless work for capital, and an urgent insistence on being able to control and direct our own activity, has simply not happened.

On the contrary, most of the projects have become small businesses, nonprofit organizations, or have simply vanished after running out of energy. (I had noted originally in the book that the usual and likely outcome of nowtopian practices was to succumb to the “iron rule” of the market by conforming to small business or nonprofit models. That is, the longer you “succeeded” the more likely that you would have to become a “normal” business.) This doesn’t mean that other projects and initiatives haven’t emerged again and again based on the same profound social need to engage in useful, meaningful, self-directed activity that actually addresses real issues we face.

Mutual aid and solidarity are still animating forces that powerfully attract people into relationships and activities that allow them to make their lives better immediately in the here and now. They simultaneously provide a taste of how much better life could be if organized on these principles. But the more recognized, dare I say ‘spectacular,’ political expressions in the past decade have not put the work we do front and center.

Occupy came closest, and for a brief moment it seemed very hopeful as an arena in which we could contest the way we make life together every day. But that moment passed quickly, and between state repression and political confusion, the effort was not sustained. The rise of militarized police forces primarily directed against people of color is such a pressing crisis that it has thrown thousands of people into defensive action, circling their wagons as best they can against the incessant pressure of state violence.

Black Lives Matter, #Metoo, the emergence of transgender politics, all important, have not included in their stated purposes any critique of modern economic life as far as I know. The ostensible premise of these movements is focused on gaining equal rights (too often described as equal “opportunity”–a slippery evasion of a real commitment to egalitarianism), and ending state repression and patriarchal violence. Of course I support these goals, but it’s hard to imagine achieving any of it absent a much greater and more general social revolt. I’ve always felt that a key to a successful general rebellion would have to be a revolt against work and an economy based on incessant growth. That doesn’t mean there wouldn’t be a TON of work to do! It means that a convergence of social movements capable of really changing the day-to-day logic of our lives would have to reject the emptiness of “success” as this world defines it. It would have to loudly proclaim the undesirability of a “job” as a be-all and end-all of life. And clearly it would have to put the ecological crisis which is quickly becoming an existential crisis front and center—which requires that we reorganize and redesign everything we do that we currently refer to as “the economy.”

My book and the Nowtopian analysis was an attempt to locate liberatory behaviors in real-life activities, things that I think are still deeply subversive and hopeful. But the separation of most political expression from the deep critique of the stupidity of how we produce and organize the making of life is not a hopeful sign. Radical opposition to Trumpism, sexism, racism, needs to also reject the terms of wage-labor and capitalist reproduction, which themselves depend on the endless separations that a lot of identity-based politics have only served to reinforce.

RH) Is the rise of inequality evidenced in these movements (Occupy, BLM, Me Too, Housing Crisis, etc..) one of the reasons that the Nowtopian revolution “has simply not happened”?

CC) I’d say the overwhelming hegemony of T.I.N.A neoliberalism (There Is No Alternative) has more to do with it, a deep logic of markets, personal responsibility, disbelief in any role for the state beyond militarism and policing, etc., is more of the problem.

RH) You live in an apartment, in a building known collectively by its residents as the Pigeon Palace. In 2015 you were all able to stave off eviction by securing a loan to purchase the building as a cooperative. As you know I am fascinated by what is going on in Spain, with En Comu, and in Los Angeles, by the emergent constellation of citizen led organizations challenging the city for the wealthy and the developers. In this time of economic and social crisis, I’m wondering how you as an urbanist relate to the possibility of the contemporary grassroots urban politics?

CC) I am hopeful and pessimistic at the same time when it comes to grassroots urban politics. There is a real paucity of critical thinking about work, jobs, or economic planning generally.

The “managed retreat” from low-lying urban coastlines is just a small example of the enormous work we should be discussing as we ponder adaptation to climate change. Reorganizing fresh water use, rainwater management, gray water systems, etc. all point to an enormous project of urban redesign that must also include different ways of using public thoroughfares (reducing cars and promoting bikes, pedestrians, etc.), radically expanding urban agricultural efforts, reorganizing distributed energy production and distribution with solar, wind, and tide, etc. etc.

A politics promoting an urban commons, in which we slowly but surely provide more and more things as basic rights to everyone–from free internet and public transit to water, good cooperative decommodified housing, free K-post-graduate education, etc. etc.–is an agenda that I could get behind. In bits and pieces this broad urban ecological commons is already emerging but so far lacks any unified or coherent political voice.

I’m pessimistic when I realize that to get to the interesting agenda that I’m hoping for will take an arduous slog through institutions that up to the present have been dedicated to managing cities to assure the accumulation of capital in private hands, and to control, repress, and mystify poor populations so they don’t assert themselves collectively. I have little stomach for the pseudo-democracy that we have to overcome to build something that might actually feel like a real democracy.

RH) What are you up to today?

CC) I co-direct Shaping San Francisco which is a multi-faceted project. It involves a twice-annual calendar of Public Talks, walking and bicycle tours, and an ever-expanding digital archive of Bay Area history. We specialize in social movements and dissent, labor and ecological history, housing, transit, neighborhood histories, and much more (the archive at Foundsf.org has over 1800 screens with thousands of photos, video clips, and more). I write my blog (nowtopians.com) from time to time, but given the growing usurpation of online communications by Facebook and Twitter, my sense of urgency about publishing on my blog has diminished and I only post between a half-dozen and a dozen entries a year now. But they reflect what I’m thinking about, what I’m reading, what I’m trying to puzzle through.

I do some adjunct teaching at USF, I guest lecture a lot, I ride my bike as transportation, and I try to get out and walk at least two hours a day. As a long-time anti-work proponent, I try to live up to my advocacy by not being busy all the time. As it turns out I tend to get a lot done—writing, reading, producing—but because I spent so many years of being aggravated by stupid busy-work, I’m hyper-efficient in the time I do work. So I get a lot done and still have a lot of time to lay around, watch sports, read magazines, walk the hills of the City, and eat healthy fresh food we prepare at home every day!

Leave a comment